In May 2013, I wrote an essay entitled Dante’s Divine Comedy and the Divine Origins of the Free Market. In the blog comments that followed, I suggested that Dante’s ranking of the seven deadly sins—in particular, the sequence by which he distinguished less serious from more serious sins—reflected insights that we share as libertarians, regardless of our status as atheists, agnostics, or Christians.

In this essay, I will flesh out that suggestion; I will show how Dante and aspects of the medieval Catholic theology that shaped his views had more in common with libertarian beliefs than the beliefs of many modern-day Christians, who have been infused with a puritanical—and even Manichaean—attitude about the natural world and its bounty and beauty. Indeed, the perceptions about the natural world shared by the theologian Thomas Aquinas and some of today’s libertarians may help explain why libertarianism resonates so deeply with Catholics, Jews, and other minorities—including Native Americans and members of the gay community. All of these groups instinctively understand that the inner state of a human being—one’s humanity and status as an individual—is more important than superficial differences that only appear to distinguish one person from another. In this sense, they mirror Dante’s understanding that the deeper, less visible “sins” of humanity are far more destructive than outwardly observable behaviors and conditions. And while this may appear to gloss over instances where outward manifestations of “sinful” behavior reflect an evil root within the inner man—it is nonetheless important to understand how inner states of being such as pride, envy, and wrath cause more harm than the outwardly visible manifestations of greed, gluttony, and lust.

And as a note to my atheist readers, I ask you to suspend your disbelief in the concept of sin so that you can share some valuable perceptions about the medieval roots of our forward-looking libertarian philosophy. If it helps, think of sin as an offense or shortcoming. For this essay, I used John Ciardi’s translation of the Divine Comedy because it reflects the terza rima of Dante’s Italian. It is available through Kindle Books. Dante Alighieri (2003-05-27). The Divine Comedy. NAL.Trade. Kindle Edition.

The Divine Comedy and the Seven Deadly Sins of Catholic Teaching

Dante Alighieri was born in Florence in the year 1265, and he was busy working on the Divine Comedy during the first two decades of the 1300s. Originally entitled simply La Commedia, it was acknowledged as “divina” some years later by Giovanni Boccaccio, who greatly admired it—so much so that he made a complete copy of it with his own hand as a gift to his friend, the poet Petrarch. Dante’s poem comprises 100 sections, called cantos, and these are grouped into three main parts – the Inferno (the first 34 cantos), the Purgatorio (33 cantos), and the Paradiso (33 cantos). We will bypass the Inferno—where Dante vents his spleen by placing numerous historical figures, frequently his enemies, in attitudes of eternal suffering that reflect his vengeful judgment upon them. Instead, we will focus on the Purgatorio, where he explores the progressive purgation of sin and guilt from the human soul.

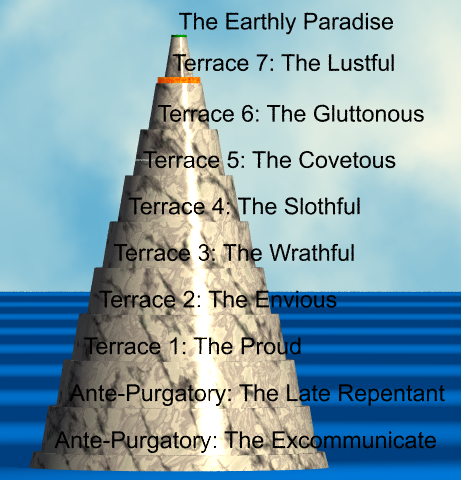

Before going further, let’s explore a few basics about Catholic teaching. It is important to understand that Purgatory is an existential condition (or place) where sinners—who already have been forgiven for their transgressions—must “work out” the remaining temporal (time-based, or earthly) penalties for their sins—and their guilt—before being allowed to enter into the state of Paradise with its direct experience and vision of God. This purgation (therapy?) is necessary for those who have not fully completed their penance during the time when they were alive on earth, i.e., their temporal punishment. In the Divine Comedy, Dante depicts Purgatory as a physical mountain located in the ocean of the Earth’s Southern Hemisphere. This mountain consists of a series of stepped terraces—with each successive terrace built on top of the one beneath.

At the base of the mountain is an area designated collectively as Ante-Purgatory. This is where various souls—consisting of the excommunicated, the indolent, the unshriven (those who have not yet confessed their sins and been prescribed a penance), and the negligent rulers—are detained until they are ready to begin climbing the mountain. During this climb, they will purge their souls and proceed from the lower terraces, where they work out the most damaging sins, to the higher terraces, where they work out their increasingly less damaging transgressions. The accompanying diagram illustrates the levels of Purgatory—beginning with the sin of pride at the lowest level, surmounted by envy, then wrath, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and finally by lust, which is conceived as the least damaging of the sins. At the very top of the mountain of Purgatory is the Earthly Paradise, from which the souls are to be taken to the Celestial Paradise depicted in the third part of the Divine Comedy, the Paradiso. On each terrace of Purgatory, the souls must confront and contemplate an example of the specific virtue—or remedy—that is the opposite of the sin depicted on that terrace.

Dante scholars recognize that the ranking sequence indicates Dante’s perception that the seven deadly sins can be organized in a three-part hierarchy:

- The sins of lust, gluttony, and greed are examples of immoderate (too much) love.

- The sin of sloth is an example of insufficient (too little) love.

- And the worst sins—wrath, envy, and pride—are examples of bad love, the perversion of love into something that destroys. I am not sure, but we might even wish to conceive of these sins as the undoing of love, the negation of love.

It is my belief that by grouping the sins in this way, Dante reveals something of a libertarian streak in his character—one that mirrored Catholic teaching before it became infected with the short-sighted and trendy socialistic bias of so many Catholic leaders.

Instead of working our way down the list by addressing the least serious sins first, let us instead follow the example of Dante and begin our exploration at the bottom—with the most dangerous and damaging of the sins: we will begin with the worst kind of “bad love,” the sin of pride.

Pride: The Most Damaging Sin (Canto X)

For Dante (and Thomas Aquinas), pride is the worst, deepest, innermost sin—and consequently the most damaging. The souls he describes on the terrace of pride are bowed down under the weight of their sin, circling the terrace and contemplating both their prideful sin and its opposite virtue, humility.

Look hard and you will see the people pressed

under the moving boulders there. Already

you can make out how each one beats his breast.O you proud Christians, wretched souls and small,

who by the dim lights of your twisted minds

believe you prosper even as you fall—

For Dante and Aquinas, pride does not mean a justified feeling of accomplishment—although he acknowledges the foolishness of delusions of grandeur. After all, he calls them “wretched souls and small.” Instead, pride is the refusal of a creature to “stay within his essential orbit” and acknowledge the dominion of God. It is both the first and the worst sin. From a libertarian perspective, this kind of pride is a state of mind by which the proud person puts himself above, or in front of, other people—discarding a peer relationship. By stepping out of the “orbit” that places him at the same level as other human beings, he takes on a worldview that places him above other people—usurping the ruling position of God, of having dominion over others. It is a state of mind that debases other human beings so that they are less than you. Consequently, it is the sin with the highest potential for damage. As Lord Acton warned in his letter to Bishop Creighton, “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

As libertarians, we would say that the desire for dominion over others is the root from which grows every dictator, thug, politician, and—wait for it!—voter that seeks to control others by means of state power. It is the attitude that puts a man above his fellows and encourages him to order them about by force. It lies behind aggression and exempts the sinner from the “rules” that govern the rest of humanity—placing him in the role of archon, caesar, dictator, politician, and bureaucrat. It is the opposite of a peer-oriented, anarchic state of mind—a word that derives from the Greek word for anarchy—in its etymological sense meaning, quite literally, “no archon” or “no dictator.” As so many libertarian writers have explained, we libertarians have nothing against the concept of governance—i.e., self governance, mutually respectful interaction, forethought, and planning. All of these together correspond to the “spontaneous order,” which we value highly.

Pride is the origin of all political systems because all of them are designed to enshrine the process of telling other people what to do and forcing them to do it—and the dictatorship of one person is intrinsically no different from the “dictatorship of the people” as expressed in the concept of democracy, under which a silly show of hands subjugates a minority to the whims of the majority—subjecting the most informed to the least informed, one man enslaving another: vox populi, vox dei; the voice of the people is the voice of God. If God is truly the unique authority over all men, then all attempts to wield this authority in God’s place are—by definition—blasphemous, damnable attempts to overreach one’s position as a human being. If you subtract the concept of God, what do you have left? Answer: a violation of the nonaggression axiom defined by Murray Rothbard in his books, For a New Liberty and Ethics of Liberty. Aggression is a denial of the fundamental basis of libertarianism—which requires treating each person as an end in himself and not as a slave to a dictator or an organized mob of voters.

With this understanding, we libertarians can appreciate Dante’s recognition of pride as the deadliest of the seven deadly sins. We will also discover that pride literally infects the other two “worst” sins of Purgatory—the sins of envy and wrath. We can even say that pride “fuels” both envy and wrath, giving them their acid bite and vastly increasing their intensity and scope of destruction. And by the way, Dante admits that his most besetting sin is pride. After all, what is his harsh judgment of his enemies, whom he places in the Inferno, but an instance of usurpation in which he metes out God’s judgment?

Envy: Greed Infused with Hateful Pride (Canto XIII)

To libertarians, it should not be surprising that the sin of envy holds a place so close to the bottom of the ethical rubbish heap—rubbing shoulders with the deepest sin, pride itself. This is not a coincidence, even though this placement collides head-on with the envy-glorifying spirit of our times. Indeed, today’s topsy-turvy moral-political alchemy has inverted our understanding of ethics; using the methods of medieval thaumaturgy, today’s envy-inspired moralists have transmuted what was, for Dante, the most deadly sin, bar one, into a modern-day virtue. To some degree, every politician of our time, with the exception of Ron Paul, genuflects at the altar of envy. They share the low impulse that drives today’s Mr. and Ms. America—not to mention the rest of the planet. Much as an upside-down crucifix serves as a symbol of Satanic ritual, the high regard in which most people hold envy reveals an allegiance to dark-side-inspired “anti-ethics.” And the proponents of the social gospel are the high priests of this cult.

And envy is based on hate—or so Dante tells us. For he names love (caritas) as the virtue that opposes (and thus cures) the sin of envy. We know this because the first words heard by Dante as he emerges onto this terrace are the words (in Latin) spoken by Jesus’ mother Mary in the Gospel of John as she cried out at the wedding feast in Cana of Galilee: Vinum non habent (They have no wine!). In that Gospel story, Mary was animated not by envying the condition of others. Instead, she was moved by her love (caritas) for others and concern for their happiness. So she pointed out their lack of wine to drink. And of course, in response, Jesus performed his first miracle—transforming water into wine.

As the ultimate rebuke to the Temperance Movement, this is instructive. It is a sentiment of which H.L. Mencken—an outspoken lover of beer—would heartily approve. In his Notes on Democracy, he wrote the following:

The sea-sick passenger on the ocean liner detests the ‘good sailor’ who stalks past him a hundred times a day, obscenely smoking large, greasy, gold-banded cigars. In precisely the same way democratic man hates the fellow who is having a better time of it in this world. Such, indeed, is the origin of democracy. And such is the origin of its twin, Puritanism.

More succinctly, he defined Puritanism as “The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” In this way, Mencken explores its close linkage with envy. For what is Puritanism if not envy of (and a desire to destroy) the joy of others? Today’s Puritans carry the torch of their philosophical ancestors by persecuting joyful deviancy wherever they find it. For example, the Puritans of the Left abhor the fat wallets of the economically successful. And the Puritans of the Right? They spend an inordinate amount of time worrying about the pudenda of the sexually adventurous. By alternating the manipulation of fear and envy, says Mencken, politicians stampede their followers into just about anything. The democratic man “…oscillates eternally between scoundrels, or if you would take them at their own valuation, heroes. Politics becomes the trade of playing upon its natural poltroonery—of scaring it half to death, and then proposing to save it.” It is the inspiration of movements such as Prohibition, the War on Drugs, and Equality fetishists. Envy. Envy. Envy. The root of this mindset.

Perhaps for this reason, on the terrace where envy is purged, Dante’s sinners are depicted with their eyelids sewn shut by wires. It is their punishment for misusing the gift of sight. Blinded, they lean upon and support each other as they never did in life. Even the hue of the stone of this terrace is the color of a bruise. Why? Because the envious were always bruised by seeing the good fortune of others.

And don’t we have daily evidence of this truth? The envious are the first to accuse others of selfishness and greed. But as Shakespeare would say, “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” For what is envy if not the sin of greed made more intense and destructive by infusing it with a hatred inspired by pride? It is a hybrid of all three. Vicious and ugly, it is greed on steroids. Take away the hate and pride, and you have simple avarice, or greed. Envious people are, quite plainly, greedy. And they do not stop at merely wanting more, as run-of-the-mill avaricious people do. They do not limit themselves to enjoying more of life, of joy, of sex, of friendship, or intoxication with wine and beer and drugs. No! They want to take away and stamp out what other people have and enjoy. Envy is greed made ugly. For greed itself is almost innocent by comparison. Greed is an impulse to be piggish about objects, ownership, profligacy, and joyful experiences—more, more, more! But envy is savage denial. It is not merely wanting to have more friends, more wine, or five cars instead of one. It is wanting to take away what others possess. It does not merely want. It hates as it wants. And I think envy would be satisfied if it never obtained anything. It merely wants to end others’ enjoyment of whatever they have. It joins forces with the sin of pride—putting itself above all others—and then ordering others to empty their pockets, sating its desire to rule. With its icy root of hatred, it gains that particular coloration we understand in the phrase “green with envy.” I suspect that behind every wealth-redistributionist is a Puritan. Such people never create wealth or joy; they only know how to take it from others.

Wrath: Anger Infused with Pride (Canto XV)

Upon climbing up to the smoke-filled terrace of wrath, the next sin to be explored, Dante is presented with examples of meekness, the virtue that is set in opposition to the sin of wrath, which is sometimes described as vengefulness. He notes that the acrid smoke of wrath stings the eyes and blinds the soul to reason—ultimately dividing men against each other. The impulse to attack others out of wrath often seems justified, but among the examples of meekness that Dante chooses to explore is the ability to calmly reprove, or correct, someone by using the powers of human reason instead of a fist or hurtful words of anger. As an example, he leans on the Gospel of Luke (Luke 2:43-52), when the 12-year-old Jesus was inadvertently left behind in Jerusalem. Jesus’ parents returned to the city and conducted a three-day search for him. At last he was found in the temple—asking questions and learning from the teachers there. And Mary, instead of shouting and striking out, expressed the anxiety that she and Joseph had felt—appealing to Jesus’ ability to empathize. Of course Jesus argued that he was doing exactly what he should be doing, which of course confounded them.

So what does this have to do with libertarians? In our analysis of ethics, politics, history, and the effects of various legal and economic systems, libertarians have consistently expressed esteem for logic and reason. Armed with principles that are openly stated, questioned, and pursued in the face of available alternatives, libertarians have been accused of being cold and exercising heartless reasoning and logic. Perhaps if we tempered our analysis with a dose of Dante’s humility and shared our need to discover truth, we would be more successful in attaining our ends. The Socratic method can go a long way in changing the minds of some people. But not everyone: the world is populated by propagandized statists. Some of us needed the sledgehammer treatment of Ayn Rand to break through our thick skulls; I confess that I am one of these hard cases. It is perhaps instructive that the most successful libertarian of his time, Ludwig von Mises, was also known for his well-mannered behavior—even though he had quite a temper and felt his ideas with great intensity. Nonetheless, he quietly, relentlessly pursued his research and writings despite a life full of dangerous obstacles, ignorance, willful indifference, and disrespect. Even better, his student, Murray Rothbard, was well known for his joyful openness and willingness to (meekly?) converse with his students in convivial nightly gatherings. There is a lesson here for us libertarians—even though I enjoy a good rant as much as the next guy.

Sloth, or Accidia (Canto XVIII)

Up to this point, the poet has explored examples of “bad” love: pride, envy, and wrath. Now he explores the sin of “insufficient” love, or sloth. For Dante, sloth is not simply wallowing in bed on Saturday morning—even if this is the first thing to come to mind. Instead, the slothful are those who recognize the good but are not diligent in pursuing it—always finding reasons for delay, usually to their own undoing. The remedy for sloth is holy zeal, and one of Dante’s examples comes from the life of Mary. He relates how she rushed to tell her cousin Elizabeth the amazing news of the annunciation, brought to her by the angel Gabriel: Ave, Maria. Gratia plena! (Hail Mary, full of grace…). Dante recounts how Mary ran to Elizabeth to tell her the news of her pregnancy. Consequently, in this part of the poem, Dante tells us that the penance (therapy) of the slothful is to rush everywhere without ceasing. The souls don’t even pause to answer Dante’s question about which way he should go to reach the next terrace of Purgatory; one of them simply shouts back the directions while continuing to run forward.

“Faster! Faster! To be slow in love

is to lose time,” cried those who came behind;

“Strive on that grace may bloom again above.”“O souls in whom the great zeal you now show

no doubt redeems the negligence and delay

that marred your will to do good, there below;This man lives— truly— and the instant day

appears again, he means to climb. Please show him

how he may reach the pass the nearer way.”So spoke my Master, and one running soul

without so much as breaking step replied:

“Come after us, and you will find the hole.

I think every libertarian has shared the energized experience of discovering the philosophy of freedom—regardless of the source that led to the discovery. Upon first encountering the alternative to collectivism, which is drummed into our heads from the womb to the tomb, many of us begin to study the theory and ethics of liberty in an almost compulsive way. And we talk about it incessantly—much to the annoyance of friends and relatives. We’ve all been there. So perhaps sloth, or accidia (in Dante’s Italian, which derives from the medieval Latin word acedia), is not the number-one sin among genuine libertarians.

Avarice or Greed (Canto XX)

Compared to the sin of envy, avarice is relatively simple and innocent. It can indeed cause damage to ourselves and those around us—as any monomaniacal focus can. It is unbalanced, immature, inconsiderate, and restricted. It funnels desire and appreciation into a single dimension that subordinates everything to the narrow pursuit of acquisitions. And yes, it too often fails to perceive the relative condition of others around us. But it is more a kind of boorishness than anything else—a misguided desire to have more—rather than a desire to harm others. That is why—by comparison—the sin of envy is so much more destructive and dangerous in Dante’s assessment: for envy combines avarice with virulent hatred and pride (the desire to place oneself over others).

Consequently, Dante levies upon the sin of greed a much less severe judgment: he places it among those sins characterized as examples of “immoderate” or “too much” love instead of categorizing it as “bad love.” In contrast to envy, avarice contains none of the seething resentment or the poisonous wish to destroy all who possess something we desire but do not have.

In Dante’s poem, the terrace of avarice is very crowded. All of us, to some degree, have experienced it at one time or another. And I would look with great suspicion on anyone who denied being susceptible to it. I look with even more suspicion on those who are determined to wipe it out by using the violence of the state.

All human beings desire to “better off” than their current condition. It is one of the apodictic insights of the economist Ludwig von Mises. This desire is inborn. After all, as Madonna taught us with her music, we are material beings. Our survival is predicated on converting matter into energy and back again to sustain our existence. Consequently, acquisition is a natural, life-sustaining impulse, or instinct. Yes, it must be trained and refined—as is the case with all of our instincts—so that it truly serves our needs and rational goals as Ayn Rand taught (before she cast libertarians into outer darkness). It is part of a matrix of behaviors that help us to develop mutually beneficial relationships. But the desire to thrive is not evil in itself. It is fundamentally life-sustaining and therefore good. It is not the equivalent of greed. Greed is a tragic expression of the need to improve our condition because it overemphasizes acquisition as the only path to a better life. It is a one-dimensional response to the multi-dimensional need to thrive. It is an over-simplified “answer” (to wrong one) to a complex question. But it requires maturation and discussion and training—not government-sponsored coercion—to outgrow.

And what is the remedy for avarice? To me, Dante’s answer is more complex than just attaining a state of abject poverty. Here are a few more verses from his poem:

And walking thus, I heard rise from the earth

before us: “Blessed Mary!”— with a wail

such as is wrung from women giving birth.“How poor you were,” the stricken voice

went on,“is testified to all men by the stable

in which you laid your sacred burden down.”And then: “O good Fabricius, you twice

refused great wealththat would have stained your honor,

and chose to live in poverty, free of vice.”These words had pleased me so that I drew near

the place from which they seemed to have been spoken,

eager to know what soul was lying there.The voice was speaking now of the largesse

St. Nicholas bestowed on the three virgins

to guide their youth to virtuous steadiness.

With careful reading, I think this validates my assertion that the remedy to avarice is more nuanced than simply taking a vow of poverty. Such a vow can, indeed, be empowering and liberating. It means you are “all in” in terms of commitment. But it is also a confession of surrender and impotence. It is an indication that you are unable to walk the fine line between total renunciation and over-acquisitiveness. It is a confession that you are unable to tolerate the ambiguities and grey areas of living a multi-dimensional life that fully comprehends and defines a positive relationship with the material world. How do we know this? The first words Dante hears on the terrace of avarice are the following: Blessed Mary. And these words are delivered “with a wail such as is wrung from women giving birth.” And while Dante also mentions the refusal of the Roman consul and general, Fabricius, to take a bribe as an example of virtue, he also mentions the generosity of St. Nicholas.

To explain this, let’s recall that Mary would not have been able to give birth to Jesus in a stable had someone not first owned that stable. And it would not have existed had it not been built as a result of devoting time and resources and acquired property into its making. Furthermore, Dante’s mention of the three virgins and St. Nicholas is a reference to a legend in which St. Nicholas gave a dowry—a purse of gold coins—to each of three virgins who were the daughters of a poor man. Because the father was unable to supply a dowry for each of them, their prospects for marriage—in that time—were dim. There is even the possibility that they would have been unable to earn a living outside of prostitution. So the generosity of Nicholas lifted them out of an uncertain and dismal future. Generosity is as much a remedy for avarice as any vow to poverty. But it presupposes both production and wealth accumulation. As Dante shows in additional passages that explore the twin—and equally damaging—human failings of both hoarding goods and wasting goods, the path that demarcates a balanced relationship between acquisitiveness and renunciation is neither smooth nor easily discernible in all circumstances. Dante thus shares an understanding that is woven into the fabric of libertarianism.

So while holy poverty is the simplest answer to the sin of greed, for Dante, the remedy also seems to encompass the process of giving birth—the act of creation itself. And creation—as in the case of the Virgin Mary giving birth—is a process that must, by its very nature, take into account the material world. And it also encompasses the spirit of generosity, of giving, as the example of St. Nicholas shows. Need we say more? Dante, lead us onward!

Gluttony (Canto XXII)

Dante’s first encounter on the terrace of the sin of gluttony is with a tree laden with fragrant, delicious fruit. This is a clear reference to the Book of Genesis and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden (the other tree in Eden is the Tree of Life). And a voice cries out warning Dante (and Virgil, his companion) not to eat:

But soon, in mid-road, there appeared a tree

laden with fragrant and delicious fruit,

and at that sight the talk stopped instantly…… The poets drew nearer, reverent and mute,

and from the center of the towering tree

a voice cried: “You shall not eat of the fruit!”Then said: “Mary thought more of what was due

the joy and honor of the wedding feast

than of her mouth, which still speaks prayers for you.

This seems to imply that gluttony is not restricted to the over-consumption of food and drink. As in the case of avarice, we are shown that an unbalanced over-emphasis on taking in too much—beyond our capacity and ability to “metabolize” either physically or mentally—is a grave error. Again, Dante refers to the virtuous example of Mary at the marriage feast at Cana—where she thought only of the comfort of the other guests instead of her own appetite. We are shown by her example that there is an outward, social focus to the relationship one has with food (and knowledge and anything else that sates our appetite). When we sit down to have a meal or to increase our knowledge through study, we can achieve a positive relationship only by acknowledging the social dimension of nourishment and of learning through the acquisition of knowledge. The focus is on developing positive relationships—even though our instinct may be to first think of our own hunger and its gratification.

It is important, once again, to notice that gluttony is considered one of the less damaging sins—one of too much love—in this case, of consuming. It is not evil in itself. Indeed, as in the case of avarice, there is a natural instinct to sustain ourselves with food and knowledge. We were born to do both in order to thrive. But one must refine these skills to use them well.

The souls on this terrace of Purgatory are emaciated, with their eyes sunken in as they experience a “hunger and thirst that nothing can assuage.” They joyfully circle the terrace to overcome their quest for physical gratification and replace it with a spiritual thirst and willingness to praise God.

The sockets of their eyes were caves agape;

their faces death-pale, and their skin so wasted

that nothing but the gnarled bones gave it shape……Who could imagine, without knowing how,

craving could waste souls so at the mere smell

of water and of fruit upon the bough?

By way of example, Dante recounts the decadence of the women of Florence and recalls the tale, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, of the gluttony of Erysichthon, who sold his daughter to purchase food, consumed it, and then devoured his very own limbs. And what is the cure? A kind of abstinence that embraces the wise and appropriate ingestion of things for which we hunger and thirst:

And soft I heard the Angel voice recite:

“Blessed are they whom Grace so lights within

that love of food in them does not exciteexcessive appetite, but who take pleasure

in keeping every hunger within measure.”

Once again, Dante is explaining that a balanced, beneficial approach to what we seek is the best route to satisfaction. As libertarians, we acknowledge this as we choose rationally in our self-interest—which tends to work out to the best interests of others as well. That’s why Ayn Rand wrote so extensively on rational egoism and rational selfishness. Likewise, the libertarian economist, Ludwig von Mises, devotes energy to his discussion of time preference in his treatise, Human Action. All of these discussions take into account the consequences of human action, and as a result, we can see the sharing of concepts between Dante and key libertarian writers. There is a benefit and a cost for everything—even if it is the opportunity cost of doing one thing instead of something else.

What more can we say of gluttony and libertarians? Libertarians are now fighting the politically connected agri-business of our time. They are questioning everything: the diabetes-producing food pyramid (hmm, any resemblance to Mount Purgatory?) versus the paleo-diet and other high-fat diets; the reversal of opinion about naturally saturated fats; concerns about the way chickens and pigs and cows are mistreated in factory-farms and the negative impact of this penned-up existence and the regular injections of antibiotics and growth hormones—not only on the animals but on the people who consume these products; the growing popularity of outlets such as Whole Foods; the nutritional and economic merits of local micro-farming versus the politically based overemphasis on so-called economies of scale (they aren’t economical); the growing popularity of organic farming; the raw-milk movement; and a host of other nutritional alternatives. All are examples of libertarians combating the government-touted diet that has transformed the topography of America with an obesity epidemic. Americans are re-learning something important: sometimes quality over quantity is not just an abstraction. It is the difference between gluttony and genuine nutrition, and libertarians are a big part of this movement away from quantitative gluttony.

Lust (Canto XXV)

Finally, we come to the last and least of the seven deadly sins—lust. And for Dante and Catholic teaching, lust is not the same as desire. The sin of lust is an inordinate craving for or indulgence of carnal pleasure. Considering the sensitive position occupied by lust in our puritanical yet simultaneously over-sexualized culture, Dante’s evaluation of lust as the least deadly of all the sins may seem surprising. But like the other two sins categorized as examples of “too much love” (avarice and gluttony), Dante views it as a kind of superficial misdeed whose evil does not penetrate deeply into the soul in the way that pride, envy, and wrath fester at the heart and twist the soul, around which revolves the entire creature. For Dante, lust is comparatively innocent. It does not betray an evil intent. This is a commonsense acknowledgment of the life-sustaining role of sexual desire. It is an acknowledgment that the physical world is a good thing in itself, a creation of God. Again, we are talking about balance—about degree, about measure, about carefully weighed results, about sanity.

For Dante, the physical world is not to be dismissed as useless or evil or something to be left behind. It is good. To think of it as something “foreign” to our soul or even “evil” is the Manichaean heresy—and therefore anti-Christian. For the Manichaean, whose heretical belief is the ultimate expression of Plato and a natural product of the school of philosophy called neo-Platonism, which was Plato’s descendant, the physical world of the senses is unreal, contaminated, and evil in its very substance. But not for libertarians, and not for Dante! Dante shared and was influenced by the insights of St. Thomas Aquinas, who corrected the lopsided Manichaean views of St. Augustine, which unfortunately are still shared by too many people—whether Christian or not. And yes, Buddhists, in their own way, are also Manichaeans. These people view the things of this world as evil and the desires of the flesh as something to be shunned—something that is alien to their focus on spirituality. For anyone who doubts that St. Aquinas and Catholic Christianity acknowledge the physical world as God-given and good, let me suggest a couple of wonderful books. The first, G.K. Chesterton’s Saint Thomas: The Dumb Ox, is a good introduction to this topic and a joy to read. As a follow up, try the more difficult and scholarly Spirit of Medieaeval Philosophy, by Etienne Gilson. And once you have mastered these, why not dip into Aquinas himself? Summa theologiae, anyone?

Nonetheless, lust, like the other sins, is an unbalancing of something good—a failure of measure that causes disharmony. Consequently, the souls on the terrace of lust are seen in the Purgatorio as moving through sheets of flame, their desires visibly setting them afire.

And in this way, I think, they sing their prayer

and cry their praise for as long as they must stay

within the holy fire that burns them there.

For Dante, the remedy of lust was chastity, and he provides examples of chastity from the life of the Virgin Mary, namely, the virgin birth. He also provides an example from classical literature by citing Diana the huntress, the goddess twin of Apollo, who kept to the woods to preserve her virginity and drove away the nymph Helicé (or Callisto), who was changed into a bear (ursa in Latin) by Juno as punishment for her liaison with Jove and subsequently placed by Jove, as an honor, in the night sky as the constellation Ursa Major. But it is best to remember that chastity was a moderate concept. It encompassed various degrees—from complete abstinence to an active sexual relationship that followed the rules of Catholic teaching.

Some libertarians may disagree about whether chastity—as Dante envisioned it—is something to emulate, but we libertarians clearly understand that remaining loyal in our commitments and to our partners is a virtue—as are precautions against sexually transmitted diseases. In any case, we acknowledge that those who follow their sexual impulses without restraint will end up with emotional scars—if not STDs. But my purpose here is not to discuss sexual ethics. It is to show that Dante holds a reasonable view of sexuality. Being loyal to one’s partner is, for Dante, a kind of chastity—even if it is not the same as virginity itself.

Dante continues his rational (and thus libertarian?) exposition when he distinguishes between gay and straight sexuality. For as he continues to explore the terrace of lust, the only difference he cites between souls who are gay and souls who are straight is the direction in which they circle the terrace. Straight souls circle the terrace in a clockwise direction, and gays circle in a counter-clockwise direction. It’s the only difference. He makes no other judgment or recriminations—setting himself apart from modern Christians and other monotheists.

for down the center of that fiery way

came new souls from the opposite direction,

and I forgot what I had meant to say.I saw them hurrying from either side,

and each shade kissed another, without pausing,

each by the briefest greeting satisfied.(Ants, in their dark ranks, meet exactly so,

rubbing each other’s noses, to ask perhaps

what luck they’ve had, or which way they should go.)As soon as they break off their friendly greeting,

before they take the first step to pass on,

each shade outshouts the other at that meeting.“Sodom and Gomorrah,” the new souls cry. ..

Lust is lust, and the rest is simply detail. There is no stigma—none of the Puritanical horror that characterized American culture until recently. For Dante, it is simply a matter of circling to the left or right. Just as important, the souls of gay and straight penitents act in complete good faith and love toward one another—exchanging a holy embrace across their divergent paths of sexual preference—crossing the double-yellow line of the traffic pattern on this terrace! Each is but one form of lust—with only a word—a vocal puff of air—to distinguish them. And the only way to leave this terrace is to be purged of all but a holy love—enabling the soul to pass through the flame that purifies, finally to emerge and climb to the Earthly Paradise atop Mount Purgatory.

Whether or not you agree with the concept of sin—and libertarians have other words for the same thing—I bring it to your attention because—as with so many other aspects of the Divine Comedy—it calls to mind the libertarian vision of self-ownership and self-determination. In particular, it reminds us of Professor Robert Nozick’s famous phrase, coined in his brilliant book, Anarchy, State, and Utopia: “capitalist acts between consenting adults.” And to put that phrase into context, it is important to remember that it is the socialists who are the enemies of all minorities and champions of none. Nozick used his famous phrase as part of a more complete statement: “the socialist society would have to forbid capitalist acts between consenting adults.”

Conclusion and Encouragement

Having completed our lightning-fast tour of libertarian themes in the Divine Comedy, I encourage my fellow libertarians and voluntaryists to explore this poem on their own. Like other expressions of the medieval world specifically and of other historical periods in general, it can be a wonderful source of reflection and inspiration. Why? Because the voice of the individual and the desire to exercise free choice (liberum arbitrium) are fundamental aspects of humanity. They are the infrastructure of human reality. They can be identified and heard in the voices of people from any historical period because the concepts of self-ownership, liberty, and the underlying truth of the libertarian non-aggression principle cannot be denied or ignored or suppressed or expunged from what is human as long as it is humanity that is the object of our exploration.

Upon reading an early draft of this essay, my brother suggested that I emphasize something fundamental to the nature of Purgatory itself that is made clear throughout Dante’s poem: the penitents in Purgatory love being there. Whenever they speak to Dante, they are always anxious, always in a hurry, to return to their purgation. They want to learn how to be free—free from compulsions. They want to learn about and gain the power to control themselves, which they define as freedom. There is nothing they would rather do. Further, they do not regret their pains in Purgatory; for in conquering sin, they self-actualize and move upward from terrace to terrace, more fully realizing with every step that they belong with God. Or as Dante put it, at the beginning of the Purgatorio itself:

…Now I mean

to lead him through the spirits in your keeping,

to show him those whose suffering makes them clean.By what means I have led him to this strand

to see and hear you, takes too long to tell:

from Heaven is the power and the command.Now may his coming please you, for he goes

to win his freedom; and how dear that is

the man who gives his life for it best knows.

Dante Teaching in the dome of the church of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence.

Postscript: Dante on the Creation of Space-Time and the Big Bang

This last bit is outside the scope of the essay, but there are some remarkable perceptions about the nature of the universe that are too good not to relate. I will restrict myself only to Dante’s conception of space-time and what can be seen as a reference to the original “singularity,” or Big Bang.

The following passage from Canto XXIX of the Paradiso bears an uncanny resemblance to scientific discussions of the Big Bang and the idea of the gravitational singularity that obtained as the initial state of the universe, except it is better:

so long did Beatrice, smiling her delight,

stay silent, her eyes fixed on the Fixed Point

whose power had overcome me at first sight.Then she began: “I do not ask, I say

what you most wish to hear, for I have seen it

where time and space are focused in one ray.Not to increase Its good— no mil nor dram

can add to true perfection, but that reflections

of his reflection might declare ‘I am’—in His eternity, beyond time, above

all other comprehension, as it pleased Him,

new loves were born of the Eternal Love.Nor did He lie asleep before the Word

sounded above these waters; ‘before’ and

‘after’ did not exist until His voice was heard.Pure essence, and pure matter, and the two

joined into one were shot forth without flaw,

like three bright arrows from a three-string bow.

It should be noted that the Italian word Dante used for this “Fixed Point” is punto. In mathematics, it is the abstract non-dimensional point. It has no measurement of width, height, or extension in space or time. It is a pure abstraction of a position. Is this really so different from the singularity that cosmologists claim is the source of all things?