In the middle of July 2018, President Donald Trump said in an interview that he was “not happy” with the Federal Reserve nudging up interest rates and threatening economic growth in the United States. At the recent Jackson Hole, Wyoming, meeting of global central bank leaders, the Federal Reserve chair, Jerome (“Jay”) Powell, said the Fed board would continue to act independently of politics and move interest rates up to ensure a stable economy with limited price inflation.

Lost in the exchange was one simple question: should it be the business of any central bank to be targeting or setting interest rates, or should this be the business of the market forces of supply and demand, as with any other price in the economy?

Market Prices Coordinate Supply and Demand

Let’s recall what it is that market-based prices are supposed to do. First, they are meant to bring the two sides of any market into coordinated balance — that is, to bring the buying plans and desires of willing demanders into balance with the producing and selling plans and desires of willing suppliers.

When a price is too high, it means that the amounts of a good that producers are offering on the market are too high for the buyers to be willing and able to purchase all that is being supplied. Facing a surplus of unsold inventories in excess of any planned levels, sellers competitively reduce the price of the good to entice demanders to purchase more.

If the price is too low, it means that the amounts of any good that producers find profitable to offer on the market are less than the quantities that interested and willing buyers would like to purchase. This shortage of a good tends to bring about a competitive bidding up of the price to induce sellers to produce and market more of it.

Market Prices Emerge Out of a Discovery Process

Thus the competitively induced movements of prices up or down bring about the required buying and selling adjustments to reestablish coordinated equilibrium in and across markets. But by how much should prices adjust in one direction or another? The answer is that nobody knows independently of the actual bids and offers of demanders and suppliers. Who may be willing to buy or sell more of the good can only be discovered through the actual competitive market process.

The reason is that buyers and sellers on the two sides of the market do not walk around with detailed buying and selling schedules in their heads tracing out how much they would buy or sell of different goods at different prices. People only sort this out in their own minds when they must make buying and selling decisions in changing circumstances and choose among the available options based on their consumer satisfaction or producer profit opportunities.

In the lingo of the economist, people only find out their own “preference scale” and rankings in the act of making choices. If people, therefore, usually cannot predict in complete detail their own buying and selling decisions ahead of making their choices, it seems presumptuous to think economic observers and analysts possess the ability to sufficiently read other people’s minds to know the answers to all of this before those same people have made up their own minds in all their interrelated complexity.

After all, the economic observers and analysts are people not much different from those whom they are studying and whose market actions they are attempting to predict. They also usually only know and decide what it is they will do in the market when they find it necessary to make their buying or selling decisions, and therefore discover their own demand and supply preference rankings.

So what can or will be the competitive and coordinating price for a good and the actual quantities of supply and demand for it at which a market may be brought into balance is not fully knowable before the market process that brings it about. This is the reason that Austrian economist Friedrich A. Hayek referred to competition as a discovery procedure. (See my article “Capitalism and Competition.”)

Prices as the Means for Market Communication

Prices are also the market means through which all those participating in the social system of division of labor are able to communicate with each other concerning their willingness to buy and sell different goods and services. In their stylized models of “perfect competition” in the economics textbooks, many economists presume that knowledge about market supply and demand conditions are already known by all or are readily available at little or no cost.

But the fact is each of us knows very little about all the billions of other people with whom we are directly and indirectly interconnected through the global division of labor. Indeed, how many of us know anything about the vast majority of the people in our own city or community in terms of who they are, what they work at, what their interests and desires may be, or which ones might be willing and able to enter into mutually profitable trades with us given their talents and abilities compared to our own? (See my article “Some Confusions of Language in Economic Thought.”)

So how shall we find out the minimum necessary information to coordinate our desires and production abilities with all of theirs? This too is the role of market prices. They serve as the market-generated shorthand sufficient in most instances to find out what people want to buy and sell for a wide range of consumer and producer decisions.

Indeed, if a network of competitively formed prices for virtually everything that can or might be produced or marketed did not exist, it would be impossible for the degree of complex and multistaged production activities that interconnect most of humanity into one market family of global betterment.

The prices of the recent past and the ongoing present serve as the signals on the basis of which people attempt to make informed judgments about what others might be willing and able to buy and sell in the future in designing their consumption and production plans looking to a series of tomorrows. (See my article “Capitalism and How Expectations Coordinate Markets.”)

And that gets to another essential role prices play in the market: the coordination of production activities across and through time in the form of multistage supply chains of production connecting many participants in the social system of division of labor.

Coordinating Today’s Production With Tomorrow’s Market Demands

Another shortcoming in many of the mainstream economics textbooks is a failure to highlight the nature of production through time and the needed coordination to ensure a continuous flow of desired goods always available on the market. Indeed, through such successful coordination of production processes through time, it is possible for most consumers in society to forget that all production takes time for which there is always a period of production before a wanted product is available for purchase and use.

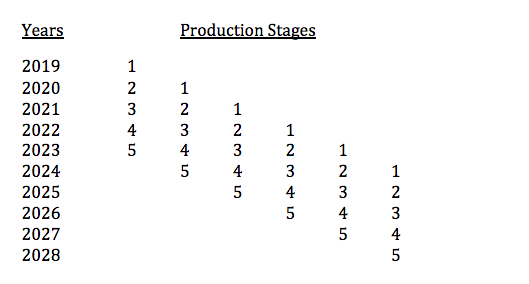

As a simplified illustration, assume there is a desired consumer good that requires five stages of production before the manufacturing is completed and the good ready for sale. Assume that each stage of the production process takes one year, so that there is a total wait time of five years for the finished good to be available.

In the table above, if demanders want the product in question to be available for purchase and use in 2023, its process of production has to begin in 2019. And if there are no existing supplies of this good from earlier production, the demanders have no alternative but to wait until it passes through each of the five one-year production stages and is then ready to be bought.

If this product is wanted for purchase and use in every year after 2023, then when the first quantities are still in the process of being manufactured during year 2, it is necessary to be simultaneously starting stage 1 of the same production process so the desired quantities will be available in 2024 as well.

If demanders want the same good in a certain amount to be purchasable in 2025, then in 2021, the initial production process must be in stage 3, the amount wanted in 2024 must be in stage 2 of manufacturing, and the amount wanted in 2025 must be beginning its stage 1 of production.

If this process is continuous, then in 2024 each of the five stages simultaneously will be in process to ensure an uninterrupted supply in future years. The production process begun in 2020 will be in its final stage in 2024; the finished product for 2025 will be in stage 4; the product for 2026 will be in stage 3 of completion; the product for 2027 will be in stage 2; and the product for 2028 will be starting in stage 1.

Consumption Cannot Be Had Without a Period of Production

If production is successfully coordinated through time in this manner, the illusion may be created that no waiting time exists for obtaining the final finished good that consumers may want to buy. Production and consumption seem to occur at the same time, making it appear as if a time dimension to production is either irrelevant or does not exist.

But this is only the case if market prices and investment decision-making have correctly matched the patterns of consumer demand at future dates, and if resources including labor and capital have been allocated across the individual periods of production in each production process in the proper sequence.

If a new automobile factory is built, the eager buyer of a car coming off this plant’s assembly line will have to wait until all the stages of constructing the first vehicle along the conveyor belt have been completed, and an automobile ready to drive away appears at the end. But once production is fully up and running after an initial period, new cars are continuously coming off the assembly line just as other, future new cars are further back along the conveyor belt in different stages of completion leading to those ready for sale.

The products ready for sale today are not the goods whose construction is being started today. Today’s ready-to-buy product started its production process sometime in the past. And the product whose production process is being started today will only be finished and available at some moment in the future when its own multistage production process has been completed.

For these intricate and interdependent production processes to be effectively coordinated, market prices must be serving as an information source about when goods are wanted and need to be manufactured in their proper sequences; and serving as income and profit incentives motivating private enterprisers to plan production, to purchase or hire the necessary inputs, and to direct these time-consuming production processes to completion.

Rates of Interest and the Saving and Investment Nexus

This gets us to where we started: whether markets or central banks should influence or set interest rates. Market-based interest rates are prices too. They are meant to bring into balance the willingness of some income earners to save with the demand of others as borrowers to use that savings for future-oriented investments that will bring forth desired goods at various times in that future.

If the willingness of some to save is greater than the desire of others to borrow at a particular rate of interest, to attract interested borrowers the interest rate is bid down, which also reduces the incentive for some income earners to save as much as they originally planned, thus reducing the available amount of savings and inducing some of those income earners to consume more in the present or directly undertake profitable investments themselves.

If the willingness to borrow is greater than the willingness of income earners to save at a particular rate of interest, those borrowers will bid up the rate of interest, leading some income earners to find it profitable to save more and consume less in the present. It will also reduce the amount of funds demanded by some borrowers as the rising interest rate makes some investments seem less profitable to undertake at a higher cost of borrowing.

Similarly to what happens with other competitively established prices, market-based movements in interest rates bring the savings and investment sides of the market into balance with each other. By how much should interest rates rise or fall to bring about this matching of the two sides of the market? There is no way to know the answer to this independently of the decisions of savers and borrowers concerning the most profitable responses to the discovery that existing interest rates are unsustainable given the discovered discrepancies between demand and supply.

Likewise, it is only through the network of market-based interest rates that information is dispersed and then integrated to facilitate the plans of multitudes of individual potential savers and borrowers separated from each other by time and space. Only market-generated interest rates enable observers to compare those possibly interested in saving with those potentially interested in borrowing.

All this is made possible through the intermediation of financial institutions that bring together all the people on both sides of this market without nearly any of them — specific savers and specific borrowers — ever knowing of each other’s existence or the reasons motivating some to save and others to want to invest.

Interest Rates Coordinate the Time Horizons of Investments

Finally, market-based interest rates coordinate the intertemporal planning decision-making of those contemplating or implementing investment in any of the stages within multi-period production processes. A rate of interest not only informs prospective borrowers about the cost of borrowing in comparison to a prospective rate of profit if an investment project were to be undertaken, it also tells them the present value of prospective investments from which they might choose.

For instance, the present value of an investment paying off $100 5 years from now at 2 percent interest is $90.50, while an investment paying off $100 but only in 10 years at 2 percent interest has a present value of $82. Suppose the rate of interest decreases to 1.5 percent. The present value of a $100 investment paying off in 5 years increases to $92.80, while the investment paying off $100 in 10 years increases in present value to $86.10.

Thus, not only would a fall (rise) in the market rate of interest influence the profitability of prospective investment projects in general, it would (all other things held the same) make longer-term (shorter-term) investments seem more profitable with the fall (rise) in the rate of interest. Thus the periods of production potentially invested in may be influenced by changes in the market rate of interest.

If the market interest rate declines because of changes in people’s savings preferences — that is, increasing their savings and decreasing their consumption spending out of earned income — this not only enables more investments to be undertaken from a larger pool of savings in general, but possibly may stimulate investments having lengthier durations to completion. That is, the time structure of investments and not simply the amount of additional investments may be influenced.

The Danger in Viewing Interest Rates as Policy Tools

Both Donald Trump and the chair of the Federal Reserve, Jay Powell, view interest rates not as market-based and market-generated intertemporal prices that serve to coordinate through the information they generate, and savings- or investment-incentivizing responses to changes in underlying real supply and demand conditions, but as policy tools to influence investment spending in the economy as a whole.

The focus is on output in general, employment in general, and the level of prices in general. In other words, the focus is on all the standard economy-wide macroeconomic aggregates that have dominated monetary and fiscal policy thinking since the Keynesian revolution of the 1930s.

But all these macro output and employment aggregates and price averages hide all the real relationships upon which market demands and supplies are based and which are kept in balance by the structure of relative prices and wages, of which market interest rates are central. (See my article “The Consumer Price Index, a False Indicator of Our Individual Costs-of-Living.”)

Just as changes in the relative prices interconnecting the demands and supplies of all the individual goods and services offered on the market keep all the various productions and resource uses in balance with consumer demands, the same coordinating role is performed by market interest rates.

Market-based interest rates keep economy-wide savings choices in balance with borrowing and investment decisions. They reallocate available scarce resources including labor from production activities closer to consumption to longer-term investment uses. They assist in determining the periods of production that are profitable to undertake, and enable the coordination of the time patterns of production sequences with those of consumer demands for goods in the future, in the manner discussed earlier.

Fed Interest Rate Policy Has Been Like a Price Control

Central bank determination or influencing of interest rates is a form of price control that prevents interest rates from revealing the truth about savings preferences and investment profitability; prevents the sharing of that information with market participants so coordination between savings available and investment possibilities may be better brought about; and potentially distorts the time structure of investment periods, so they may be inconsistent with the real savings to sustain them, given the patterned sequence of when consumers may desire goods at various times in the future.

For most of the last 10 years, the Federal Reserve has utilized its monetary policy tools to push nominal interest rates near to zero. When adjusted for price inflation by using the Consumer Price Index as a rough indicator, several key interest rates have been in the negative range for most of this time. That is, in terms of real buying power, the cost of borrowing has been, well, zero.

When government sets a market price at or near zero, it basically abolishes it as a useful indicator of the real demand for the good and the possible supplies of it based on resource availabilities and the opportunity costs of using them for one or another production possibility instead.

This means that it is not unlikely that conditions have been created for a future economic downturn typical of the business cycle: interest rate misinformation; relative prices inconsistent with underlying supplies and demands; misallocations of investable capital and labor; and mismatching of some periods of production with consumer demand and with savings choices, thus leading to unsustainable investment. (See my article “Monetary Fallacies and Inflationary Bubbles.”)

As long as politicians and central bankers consider it their business to manipulate market prices, of which interest rates are among the most essential, economy-wide imbalances and discoordinations in the market economy will keep reappearing. And no doubt “capitalism” and the profit motive will end up being tagged as the culprits, while all the time the guilty parties live and work in the halls of government offices and in central banks.

This article was originally published by The American Institute for Economic Research.