Proponents of the government’s lone-nut assassination theory in the John Kennedy assassination oftentimes suggest that those who reject the official version of what happened have some sort of psychological need to place the assassination within the context of a conspiracy. Conspiracy theorists, they say, simply cannot accept the idea that a lone nut succeeded in killing a president of the United States and a popular president at that.

I see it a different way.

When it comes to the national-security state, there are basically two groups of people, one group consisting of people with an independent and critical mindset and the other group consisting of people with a mindset of deference to and trust in authority.

For ease of expression, I will refer to the first group as the independents and the second group as the deferentials.

Over the years, I have read a considerable amount of literature relating to the Kennedy assassination. I have never encountered anyone who believes that there was a government conspiracy in the JFK murder who also believes that there was a government conspiracy in John Hinkley’s assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan or in Lynette Fromme’s assassination attempt against President Gerald Ford. Wouldn’t you think that if a person has a psychological need to look for government conspiracies behind presidential assassinations or assassination attempts, the need would be applied consistently to all presidential assassinations or assassination attempts?

So, what’s different about the Kennedy assassination?

The difference is that there are so many unusual anomalies within the Kennedy case that an independent and critical thinker feels compelled to ask, “Why?” The ability and willingness to ask that simple one-word question is what distinguishes the independents from the deferentials.

For the deferential, all such anomalies are irrelevant. All that matters is the official government version of the assassination. For the deferential, questioning or challenging the official version of a major event like a presidential assassination is a shocking notion, one that violates the deference-to-authority mindset that has been inculcated within him since he was six years old.

Examine carefully the criticisms that lone-nut proponents make of people in the assassination research community. Many lone-nut proponents mock conspiracy theories in the JFK case not because they feel there is a lack of evidence to support the theory. That is, they don’t say: “After carefully reviewing the evidence in the JFK case, I’ve concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was a lone-nut assassin.”

Instead, many of the lone-nut proponents subscribe to what I call the “inconceivable doctrine,” one that holds that it is simply inconceivable that the U.S. national-security state would have conspired to assassinate a U.S. president.

Oh sure, for a deferential it is entirely conceivable that the national-security state would conspire to assassinate a foreign president or effect a regime-operation abroad, especially if national security is at stake. In such cases, the deferential, unable to bring himself to question or challenge the legitimacy of such operations, offers his unconditional support. But for the deferential, it is just inconceivable that the national-security state would do the same here at home, even if national security depended on it.

The inconceivable doctrine, of course, dovetails perfectly with the deference-to-authority mindset.

Let’s examine this difference in mindset between independents and deferentials by considering the fatal head wound in the Kennedy assassination, a matter that is detailed much more fully in Douglas P. Horne’s 5-volume series Inside the Assassination Records Review Board. Horne served on the staff of the ARRB, an agency that was created in the aftermath of the controversy over Oliver Stone’s movie “JFK.”

On page 69 of Volume I of his book, Horne states:

Simply put, on November 22, 1963 the Parkland hospital treatment physicians observed what they thought was an exit wound, a “blowout,” in the back of the President’s head, and described it virtually unanimously in the following way: (1) it was approximately fist sized , or baseball sized, or perhaps even a little smaller — the size of a very large egg or a small orange; (2) it was in the right rear of the head behind the right ear; (3) the wound described was an area devoid of scalp and bone; and (4) it was an avulsed wound, meaning it protruded outward as if it were an exit wound.

Horne points out that this observation of the Dallas treatment physicians was reinforced by a Dallas nurse named Pat Hutton whose written statement said that Kennedy had a “massive wound in the back of the head.” (Horne, Volume I, page 69.)

She and the Dallas treatment physicians weren’t the only ones.

Secret Service agent Clint Hill, who ran to the back of the presidential limousine and covered the president and Mrs. Kennedy with his body and who had a very good view of the president’s head wound during the trip to Parkland Hospital, wrote in his written report:

I noticed a portion of the President’s head on the right rear side was missing … part of his brain was gone. I saw a part of his skull with hair lying on it lying in the seat. (Horne, Volume I, page 69.)

Or consider the sworn testimony of Sandra Spencer, the Petty Officer in Charge of the Naval Photographic Center’s White House lab in Washington, D.C., before the ARRB about one of the Kennedy autopsy photographs she developed, one of the many photographs that she said never made it into the official autopsy record:

Gunn [ARRB interrogator]: Did you see any photographs that focused on the head of President Kennedy?

Spencer: Right. They had one showing the back of the head with the wound at the back of the head.

Gunn: Could you describe what you mean by the “wound at the back of the head?”

Spencer: It appeared to be a hole … two inches in diameter at the back of the skull here.

(Horne, Volume II, pages 314-315.)

***

Gunn: Ms. Spencer, you have now had an opportunity to view all the colored images, both transparencies and prints, that are in the possession of the National Archives related to the autopsy of President Kennedy. Based upon your knowledge, are there any images of the autopsy of President Kennedy that are not included in those views that we saw?

Spencer: The views that we produced at the Photographic Center are not included.

(Volume II, page 325.)

Horne sums up one import of Spencer’s sworn testimony before the ARRB (Horne, Volume II, page 331.):

The second major implication of the Sandra Spencer deposition is that the Parkland hospital medical staff written treatment reports prepared the weekend of the assassination were correct when they described an exit wound in the back of President Kennedy’s head, and damage to the cerebellum. (Italics in original.) [Note: the cerebellum is the part of the brain that is located in the lower back of the head.]

So, what’s the problem?

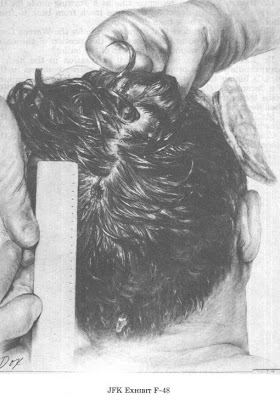

Take a look at the following rendering of the official autopsy photograph of the back of Kennedy’s head by House Select Committee on Assassinations illustrator Ida Dox in 1978:

Do you see the problem? The photo does not show a hole in the back of Kennedy’s head. It shows the back of the head to be intact.

Why is that a problem?

Because the government’s official version is that that photo correctly depicts the condition of Kennedy’s head after the assassination and, therefore, directly contradicts all the people who saw a hole in the back of the head.

Now, consider this testimony by FBI agent James Sibert, who attended the autopsy, before the ARRB:

Gunn: Mr. Sibert, does that photograph correspond to your recollection of the back of the head?

Sibert: Well, I don’t have a recollection of it being that intact…. I don’t remember seeing anything that was like this photo.

***

Gunn: But do you see anything that corresponds in photograph 42 to what you observed during the night of the autopsy?

Sibert: No, I don’t recall anything like this at all during the autopsy. There was much — well, the wound was more pronounced. And it looks like it could have been reconstructed or something, as compared to what my recollection was.” (Horne, Volume I, pages 30-31.)

Consider this testimony of FBI agent Frank O’Neill, who also attended the autopsy, before the ARRB:

Gunn: ….I’d like to ask you whether that photograph resembles what you saw from the back of the head at the time of the autopsy.

O’Neill: This looks like it’s been doctored in some way. Let me rephrase that, when I say “doctored.” Like the stuff has been pushed back in, and it looks like more towards the end than at the beginning [of the autopsy]….

***

O’Neill: Quite frankly, I thought that there was a larger opening in the back … opening in the back of the head. (Volume I, page 31.)

That’s not all.

Horne writes (Horne, Volume 1, page 78):

My own, more nuanced characterization follows. At the time the ARRB commenced its efforts, several autopsy eyewitnesses (Tom Robinson [from Joseph Gawler’s Sons, Inc. funeral home], [FBI agent] Frank O’Neill, [FBI agent] James Sibert, John Ebersole [Bethesda autopsy radiologist], Jan Gail Rudnicki [autopsy lab assistant]; x-ray technician Ed Reed; Secret Service agent Roy Kellerman; and Philip Wehle [commander of the Military District of Washington]) had given descriptions to the HSCA [House Select Committee on Assassinations] staff, or had drawn images for them, that were very reminiscent of the Dallas descriptions of the exit wound in the skull — indicating that a large portion of the back of the President’s head was missing… .(Italics in original; brackets added.]

That’s not all.

Soon after the assassination, a Dallas medical student named Billy Harper found a portion of Kennedy’s skull near the assassination site. He took the fragment to his uncle, Dr. Jack C. Harper, who took it to Methodist Hospital in Dallas, where it was photographed. Dr. A.B. Cairns, former chief of pathology at the hospital, told an investigator for the HSCA that the skull fragment, which became known as the Harper Fragment, was from the lower occipital area, which denotes the lower back of the head. The government later lost the fragment. (Volume II, page 392.)

What does a deferential do when faced with this quandary? After all, we have lots of credible people saying one thing and an official government photograph depicting the opposite.

This presents no problem for the deferential. For him, the official government photograph and the official government version of events are gospel. Any conflicting evidence is simply ignored and disregarded. For the deferential, evidence that contradicts the official story is, at worst, concocted and, at best, simply mistaken. Either way, it’s irrelevant.

For the deferential, it is simply inconceivable that the government would falsify the appearance of the back of Kennedy’s head. Alternatively, if the government did falsify how the back of the head appeared, the deferential would simply assume that the government had good reason to do so, almost certainly something to do with protecting national security.

Either way, the deferential says that we must simply trust the government. We mustn’t ask questions. We must defer to authority.

That’s how the deferential mindset works.

The independent sees things differently. His mindset causes him to ask, “What in the world is going on here?” After all, either lots of reputable people have concocted a fake story about the hole in the back of Kennedy’s head or the government’s photo falsely depicts the appearance of the back of Kennedy’s head.

Since it’s highly unlikely that all those people got together to concoct such a story, that leaves but one alternative: The government’s photo falsely depicts the back of Kennedy’s head.

Unlike the deferential, the independent wants to know why. Why would the government do that? Why would it try to hide an exit wound in the back of Kennedy’s head? What would be the point?

Well, one point would be: to hide evidence of shots being fired from the front, given that an exit wound in the back of the head obviously connotes a shot having been fired from the front.

So, the independent would ask the next logical question: Why would the government try to cover up shots having been fired from the front? Why would it want to immediately shut down the investigation by pinning the murder on a lone nut rather than exploring the possibility that other people were involved in the assassination?

That’s the way the mind of an independent works. Contrary to what the lone-nut theorists suggest, it’s not that the independent has a psychological need of a conspiracy in presidential assassinations, it is simply that the independent’s critical mindset needs a logical and rational explanation for the many anomalies in the Kennedy case.

That’s the conflict that will play out this year and afterward in discussions relating to the Kennedy assassination: the mindset of those who have independent, inquisitive, critical, and analytical minds versus the mindset of those who defer to authority and trust that the government is doing the right thing, especially in matters relating to national security.