Whenever some foreign regime that is independent of the U.S. Empire goes after dissenters, U.S. officials trot out the First Amendment to show how different the United States is. Here, people are free to criticize government officials without fear of being put in jail or otherwise punished for exercising their free speech rights, they proudly point out.

However, what goes unexplained in such pious proclamations is why so many leading executives in big American companies remain silent when it comes to America’s foreign wars, foreign interventions, coups, alliances with dictators, torture, mass secret surveillance, indefinite detention, denial of due process, Gitmo, state-sponsored assassinations, and other dark-side activities of the U.S. national-security establishment.

The reason is that every one of those executives knows that federal officials are able to retaliate against them in indirect ways for criticizing their policies and operations. Such indirect methods of retaliation can consist of IRS audits, regulatory harassment, denial of applications for mergers and acquisitions, non-renewal of radio and television licenses, and even the threat of disclosure of personal secrets acquired through secret surveillance of emails and telephone records.

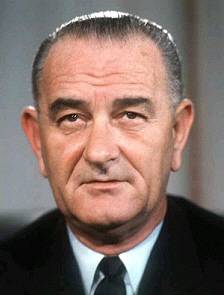

A good example of free speech nullification involved President Lyndon Johnson, soon after he became president after the assassination of President Kennedy. Johnson’s indirect nullification of the First Amendment is set forth in Robert Caro’s book The Passage of Power.

Prior to the assassination, a Dallas reporter named Margaret Mayer had begun investigating Johnson’s radio and television stations in Austin. On the evening of Saturday, January 4, 1964, Johnson telephoned her paper’s managing editor and spoke directly about what he was prepared to do if the paper didn’t stop Mayer’s investigation.

Johnson mentioned by name the paper’s publisher and board owner, its president, and the president of radio and television stations owned by the paper. He then made it clear that he was prepared to use all the powers at his disposal against them if they didn’t stop Mayer’s investigation, including IRS audits, both personal and business, as well as non-renewal of FCC licenses for the radio and television stations.

Johnson demanded a response by the next morning. The next morning — Sunday morning — the editor telephoned the president and said, “We’ll take care of the thing tomorrow” and assured Johnson that his role would be kept secret. Mayer’s investigation was shut down.

Caro provides another example, one involving not just a reporter but rather an entire newspaper, which had been critical of Johnson before the assassination. Johnson set out to stop the criticism.

The paper’s president also served as president of a local bank that was trying to merge with another Texas bank. Such mergers require federal approval. Both the Federal Reserve and the Justice Department opposed the merger. Using presidential aide Jack Valenti as an intermediary, Johnson told the paper that if it wanted the merger to go through, it would have to cease criticizing him. According to Caro, the paper became a supporter of Johnson, even endorsing him in the 1964 race. Johnson overruled the Fed and Justice and ordered the approval of the merger.

Caro provides another example of this phenomenon, one involving a Washington, D.C., correspondent for a Texas newspaper. The reporter had been critical of Johnson. Johnson telephoned the paper’s owner and mentioned Fort Worth’s Carswell Air Force Base as well as the recent decision to close the Fort Worth Army Depot. He also mentioned a project to make the Trinity River navigable for barges from the Gulf of Mexico to Fort Worth.

The paper squeezed out the reporter. Carswell remained in operation and ended up playing a big role in Johnson’s war in Vietnam. Johnson also made sure that one billion dollars in federal money went to the Trinity River project, although the project was never finished.

Today, it is hard to believe that a president, the Pentagon, the CIA, or the NSA would make these types of direct threats to any U.S. company or its executives. But they don’t have to. Everyone knows what can happen to them if they decide to publicly criticize the sordid, dark-side activities of the national-security establishment. Discretion is the better part of valor, which has to be one big reason why most executives choose to remain silent.