Government spending is out of control. In March 2021, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that federal government spending in fiscal year 2021 (which began on October 1, 2020) will come to at least $5.8 trillion, with tax revenues of $3.5 trillion, and a resulting budget deficit of over $2.3 trillion. The total federal accumulated debt will be approaching $30 trillion.

“Mandatory” government spending – the “entitlement programs” – will come to about $3.7 trillion out of all expenditures of $5.8 trillion, or 66 percent of that total. “Discretionary” spending will be over $1.6 trillion, with interest payments on prior accumulated federal debt being another $303 billion. Notice that the entitlement spending for Uncle Sam’s current fiscal year of $3.7 trillion will be larger than the anticipated total tax revenues of $3.5 trillion from all sources. The core welfare state expenses are costing $200 billion more than all of what is collected from American taxpayers. So, the government is borrowing money to cover part of the entitlement expenditures, plus all “discretionary” spending, and the interest on the national debt.

In this fiscal year, government spending will equal 26.3 percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with tax revenues coming to 16 percent of GDP, and the budget deficit equaling 10.3 percent of GDP. That is, federal government spending will be more than one out of every four dollars of the total value of national output. And the budget deficit will be more than one out of every 10 dollars of GDP.

(It also should be kept in mind that in 2021 state and local government spending is likely to be an additional $4 trillion, on top of what the federal government is spending.)

The Massive Cost of Government Over the Coming Decade

Looking over the next decade up to 2031, the CBO projects that between now and then, the federal government will spend a total of over $61 trillion, and tax away almost $49 trillion, meaning more than $12 trillion in additional deficit spending added to the national debt ten years from now, which means it will reach a total of at least $40 trillion in ten years.

Right now, the national debt burden per U.S. citizen comes to $85,000, and per taxpayer, $224,000. With an estimated population in the United States of 360 million in 2031, this means that the debt burden per citizen will have increased to over $111,000, while the debt will equal more than $500,000 per taxpayer by then.

Tens of Millions of People on the Government Dole

It should not be too surprising that with this amount of government spending a sizable percentage of the U.S. population receives monies from Uncle Sam in one form or another. In 2020, 64 million Americans, or more than one out of every six in the country, received Social Security benefits. While 80 percent of those recipients are receiving that government transfer as a retirement payment, 20 percent receive money from the Social Security Administration for some qualified “disability,” and the standards for such qualification has been eased in a variety of categories in recent years.

There are 61.5 million who are Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Over 77.8 million Americans are enrolled in Medicaid state programs, and 37 million are enrolled in the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). An additional 38 million Americans receive food stamp benefits (SNAP – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) from the U.S. government.

In other words, almost half of the population of the United States receives redistributed income and benefits – “transfers” – from the government. This does not count various forms of “corporate welfare,” such as subsidies for farmers, for instance. The agricultural sector of the economy received $37.4 billion in direct payments from the federal government in 2020.

Balanced Budgets and an Unwritten Fiscal Constitution

A good part of the reason for this was explained almost 45 years ago by James M. Buchanan (1919-2013) and Richard E. Wagner in their book Democracy and Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes (1977). In the 19th and the early 20th centuries, the United States government adhered, in principle, to an annual balanced budget rule in managing its finances. It was argued that this assured a greater degree of transparency and fiscal responsibility.

A balanced budget made it easier and clearer for the American voters and taxpayers to compare the “costs” and the “benefits” from government spending activities. Since each dollar spent by the government required a dollar collected in taxes to pay for what the government was doing, the citizen-taxpayer could make a more reasonable judgment whether they considered any government spending proposal to be “worth it” in terms of what had to be given up to gain the claimed “benefit” from it.

The trade-off was relatively explicit: Any additional dollar of government spending on some program or activity required an additional dollar of taxes, and, therefore, the “cost” of one dollar less in the taxpayer’s pocket to spend on some desired private-sector use, instead. Or if taxes were not to be raised, then it had to be explained what existing government program or activity was to be cut or reduced to supply the needed existing tax funds to be shifted into this new proposed use.

Buchanan and Wagner also pointed out that this rule was a chosen one to adhere to, or as they put it, it was an “unwritten fiscal constitution,” since there is nothing in the U.S. Constitution obligating the federal government to balance its budget on an annual basis. Instead, it was considered a wise and honest policy, since the citizens and the taxpayers would always know the real cost of whatever the government was doing.

From Balanced Budgets to Keynesian Deficit Spending

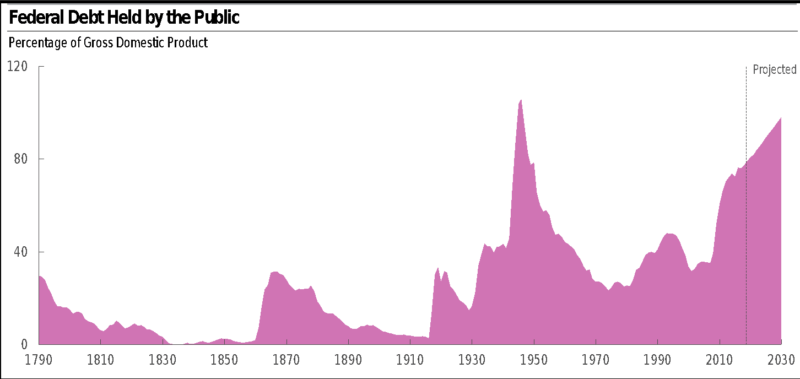

The generally accepted exception was during a time of national emergency, most frequently during a war, when the government might have an urgent need for an inflow of funds for which normal incoming taxes would be insufficient. When the “crisis” had passed, it was expected for the government to, then, run budget surpluses, and bring down and pay off the debt accumulated during the previous war. Amazingly, a graph showing the pattern of national debt as a percentage of GDP during the 19th and early 20th centuries shows that federal debt was run up during wartimes, and, then, slowly but surely almost paid off, until the next war crisis. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

However, with the rise of Keynesian Economics in the 1930s, following the publication of John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), it was argued that the government should not balance its budget each year, but, instead, do so over the phases of the business cycle. That is, during recession years the government should run budget deficits to restore and maintain full employment output in the economy, rather than wait for the market’s own natural “rebalancing” of aggregate demand and aggregate supply; the latter could be a long and difficult process, the Keynesians said, if the market was left to its own devices. Better for the government to give a fiscal “activist” hand. Then when full employment was reestablished and any inflationary pressures might emerge, the government could run budget surpluses to rein in “excess” aggregate spending and, then, pay off what had been borrowed earlier.

This new “rule” of balancing the budget over the business cycle rapidly became a generally accepted idea for fiscal policy among politicians and policy proponents in the post-World War II period. However, there has been one major problem with this alternative method of managing government taxing and spending. During the 76 years since the end of the Second World War in 1945, the U.S. government has run budget deficits in 64 of those years and budget surpluses in only 12 of them. The U.S. economy, by the way, was not in recessions for more than six of the decades since the end of the war.

Keynesianism Set Politicians Free to Spend and Spend

With the elimination of the balanced budget rule as the guide for government fiscal policy, it has been possible for politicians to create the economic illusion that it is possible to get something for nothing – or at least at a great discount of what it otherwise might cost in terms of tax dollars paid.

Politicians can offer benefits in the present in the form of new or additional government spending, but they no longer have to explain where the money will come from to pay for it. The “costs” of all that deficit spending in terms of the accumulating national debt is to be paid for by some unknown future taxpayers in some amounts that can be put off discussing until that “sometime” in the future. Thus, politicians can supply “concentrated benefits” in the present – “now” – to voting groups and avoid answering where all the money will come from to pay it back (with interest!), and precisely by whom. That can be delayed until the future, a period of time, years ahead, when someone else will hold political office and may have to deal with the problem, if they are no longer able to kick the debt can further down the fiscal road.

This is seen in Figure 1, also, with the continual growth in the debt in the post-war period due to those almost unending and continuing annual budget deficits. However, it is important to clarify one thing in Figure 1. For the period from 1945 into the 1960s, it seems as if the national debt was diminishing. But what is shown in this diagram is the national debt as a percentage of GDP. For most of the twenty years after 1945, the federal government did run budget deficits. It is just that the growth of the debt during that period was at a slower rate than Gross Domestic Product was increasing. But in absolute terms, the debt continued to rise.

Since, certainly, the 1970s Uncle Sam’s debt, both absolutely and relative to GDP, has continued to increase. Only for four years in the second half of the 1990s, when Democrat Bill Clinton was president and the Republicans held both houses of Congress were there four years of modest budget surpluses. But under George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and, now Joe Biden, the national debt has been exploding, and will continue to do so, unless there is a radical change in the politics of government spending and taxing. (See my articles, “America’s Fiscal Follies are Dangerously in the Red” and “Debt, Deficits, and the Costs of Free Lunches”.)

Representative Government a Part of a Free Society

But another factor in this has been the impact of universal voting suffrage. The right to vote has been considered an essential element and ingredient to a free and democratic society. After all, before the rise of modern democracy as a political principle and ideal, governments were in the hands of monarchs and tyrants possessing, usually, almost absolute power over the fate of those over whom they ruled.

If individuals were to have the personal freedom to be out from under the strong hand of government, and to possess their own, respective, rights to life, liberty, and honestly acquired property, and to live their lives as they peacefully chose to, then it was also only reasonable and natural for those in political power and authority to be responsible to those over whom they ruled. Hence, the idea and practice of representative government, with those in governmental office voted in by the free citizens of society and accountable to those citizens through periodic elections to, if necessary, “throw the rascals out.”

But while the democratic principle is reasonable and, indeed, institutionally desirable as an essential safeguard in a free society, “democracy” is merely the mechanism for selecting among competing candidates for appointment to positions of political authority for a given period of time. It does not, in itself, specify the size and scope of government’s responsibilities and reach within any society. As classical liberal-oriented thinkers already pointed out in the 19th century, voting majorities can be potentially just as tyrannical and plundering as non-democratically ruling minorities such as under the monarchies of the past. (See my article, “John Stuart Mill and the Three Dangers to Liberty”.)

Liberal Democracy versus Social Democracy

A society recognizing and respectful of the individual rights of the citizenry needs to restrain the reach of government through constitutional limits that clearly specify the duties and responsibilities of that government, and what powers and authorities those in political authority do not possess. This is essential so as to preserve the individual liberties of the citizenry, and not run the risk of the political regime degenerating into a democratized system of interest group plundering, in which each vies in competition or coalition with other groups to use the taxing and spending powers of the government for their own, respective, benefits at the expense of those unable to form and be part of majoritarian victories on election day.

That is why the adjective “liberal” is vital before the word “democracy,” making it clear that what is being referred to is a democratic system defined by and insistent upon the individual liberty and rights of each member of the society in terms of confining the activities of the government within a philosophy of rightly understood human freedom.

When, explicitly or implicitly, the word “social” appears before the word “democracy,” it is delineating the functions of government to include ideologically rationalized plunder, privilege, and power-lusting through a network of state interventions, regulations, restrictions, and compulsory redistributions of income and wealth. The word “social” in this context is merely softening the reality of it being a modified version of a socialist system of command and control, which narrows the range of personal choice, action and voluntary association with others on the basis of mutual consent and agreement.

While it may seem shocking and “politically impossible,” one way to limit, if not end, unrestrained government and the current system of democratized plunder and privilege is to withhold the voting franchise from anyone receiving all or a good portion of their incomes through the hands of government. And to withhold their voting right for as long as they are on the government dole in some way, shape or form.

John Stuart Mill on Political Pickpocketing

This idea, in fact, was proposed by the 19th century economist and political philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) in his 1859 book, Considerations on Representative Government (chapter 8, “Of the Extension of the Suffrage”). Mill argued that those who received “public assistance” (government welfare) should be denied the voting franchise for as long as they receive such tax-based financial support and livelihood.

Simply put, Mill reasoned that this creates an inescapable conflict of interest, in the ability of some to vote for the very government funds that are taxed away from others for their own benefit. Or as Mill expressed it:

It is important, that the assembly which votes the taxes, either general or local, should be elected exclusively by those who pay something towards the taxes imposed. Those who pay no taxes, disposing by their votes of other people’s money, have every motive to be lavish and none to economize.

As far as money matters are concerned, any power of voting possessed by them is a violation of the fundamental principle of free government . . . It amounts to allowing them to put their hands into other people’s pockets for any purpose which they think fit to call a public one.

Mill went on to explain why he considered this to be especially true for those relying upon tax-based, redistributed welfare dependency, which in 19th century Great Britain was dispersed by the local parishes of the Church of England. Said Mill:

I regard it as required by first principles, that the receipt of parish relief should be a peremptory disqualification for the [voting] franchise. He who cannot by his labor suffice for his own support has no claim to the privilege of helping himself to the money of others . . .

Those to whom he is indebted for the continuance of his very existence may justly claim the exclusive management of those common concerns, to which he now brings nothing, or less than he takes away.

As a condition of the franchise, a term should be fixed, say five years previous to the registry, during which the applicant’s name has not been on the parish books as a recipient of relief.

Applying Mill’s Principle to Our Current Welfare Recipients

Clearly, in our times, this would mean withdrawing the voting franchise from all those currently receiving Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid, food stamps, or from any other number of welfare state redistributive programs. I would suggest that the same argument could and should be extended to all those who work for the government; for as long as they are employed by the government they are directly living off the taxed income and wealth of others.

If it is said that government employees pay taxes, too, the reply should be that if you receive a $100 salary from the government and pay in taxes, say, $25, you remain the net recipient of $75 of other people’s money and are not a net contributor to the costs of government.

Extending this logic just a little further, I think that the same case could be made about all those who live off government expenditures in the form of contracts or subsidies; they, too, should likewise be excluded from voting for the same conflict of interest reasons.

Such individuals and their private enterprises may not be totally dependent upon government expenditures for their livelihood. A rule might be implemented that to be eligible for the right to vote, no individual or the private enterprise from which he draws an income should receive (just for purpose of example), say, more than 10 percent of his or her gross income from government spending of any sort.

If such a voting restriction had been in effect 100 year ago, it is difficult to see how the government could ever have grown to the size, scope, and cost that it now has in society.

In turn, if there were any way to implement such a vote-restricting rule, it is equally hard to see how the current, gigantic interventionist-welfare state could long remain in existence. Government, no doubt, would soon be cut down to a far more limited and less intrusive size.

Our dilemma, today, is that, to use John Stuart Mill’s phrase, we have a political system in which many who have the right to vote use it “to put their hands into other people’s pockets for any purpose which they think fit to call a public one.”

Unless some way is found to escape from our current political situation, to use Frederic Bastiat’s words, in which the State has become the “great fiction” through which everyone tries to live at everyone else’s expense, we are facing a fiscal and general social crisis that may truly be destructive of society in the coming years.

This article was originally published at The American Institute for Economic Research.