On December 29, the New York Times published an article entitled “How the Russian Government Silences Wartime Dissent,” which details the Russian government’s prosecution of Russian citizens who criticize Russia’s war on Ukraine. According to the article, “In the first 18 months of the war, the law scooped up a vast array of ordinary Russians — schoolteachers, pensioners, groundskeepers, a carwash owner — for punishment.” The article points out that the prosecutions have resulted in widespread “self-censorship” in which people are too afraid to speak out against the war.

Of course, nobody should be surprised over Russia’s suppression of free speech during wartime, especially given Russian President Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian bent. What I found interesting about the Times’s article, however, was the total absence of any mention of the U.S. Espionage Act of 1917, which was enacted during World War I. After all, it’s entirely possible that Russian authorities are using the U.S. Espionage Act as a model in their suppression of wartime dissent in Russia.

The purpose of the U.S. Espionage Act was the same as that of Russian authorities today — to silence war critics. To achieve that end, U.S. officials went after critics of U.S. interventionism in World War I as viciously as Russian authorities are pursuing Russian critics of Russia’s intervention in Ukraine.

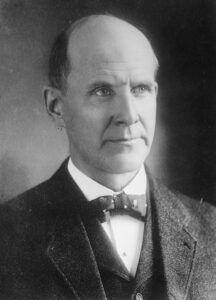

Among the most notable victims of U.S. suppression of wartime speech was Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs, who delivered a speech that “obstructed recruiting” for the war. For that heinous crime, Debs was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to 10 years in a federal penitentiary.

Not surprisingly, the Debs case resulted in the same phenomenon of self-censorship that is occurring in Russia today. Americans kept silent because they didn’t want to risk going to jail for for questioning or criticizing U.S. entry into the war.

It’s worth noting something else: The U.S. Espionage Act wasn’t repealed after World War I ended. Instead, U.S. officials kept it on the books to serve as a “standby” power. Thus, not surprisingly, U.S. officials are using this old World War I dinosaur to go after war critic Julian Assange with the same viciousness that Putin and Russian authorities are going after Russian citizens.

All that Assange did was reveal to the world some of the war crimes and other dark-side activities of the U.S. national-security state during its much-vaunted “war on terrorism” and its illegal deadly and destructive invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. The Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA were not about to tolerate that sort of thing, and so the Justice Department simply trotted out the old World War I Espionage Act to target Assange with federal criminal prosecution.

Moreover, like in Russia, the Assange prosecution has resulted in widespread self-censorship here in the United States, especially within the U.S. mainstream press, which is loathe to disclose and criticize war crimes and other dark-side practices of the U.S. national-security state. Indeed, most of the mainstream press is even afraid to come to Assange’s defense, knowing full well that the wrath of the Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA would be unleashed on them.

Russia’s current campaign of suppression of free speech can teach us a lot about the road to tyranny and oppression that the United States has taken for more than 100 years and especially since the U.S. government was converted to a national-security state after World War II.